Three days. Forty-three artists. A new gallery turns into a civic square.

From 8 to 10 September in As-Suwayda, Nova Gallery filled with painting, sculpture, installations, and mixed media. The works confronted war, injustice, and the harm inflicted on civilians. Attendance was so heavy that the space could barely hold the crowd.

“A show that speaks about war, injustice, and the violations committed against civilians. The response exceeded our expectations,” said Alaa Qutaish, a fine arts graduate and member of the Union of Visual Artists.

The curatorial through-line was clear. Paintings and sculptures drew on a local material vocabulary, from basalt tones and ash textures to pieces built from repurposed objects such as keys, tins, and old devices. The aim was not to distract from reality or beautify it. It was to face it and name it. Artists offered a civic language that puts public life first, using form, color, and scale to affirm dignity, register loss, and show a community’s capacity to act culturally and make meaning under daily pressure.

For Hanan Halabi, a Dubai-based expatriate who invested in the space, the exhibition was also a return to roots. “I wanted to connect myself with something here because I love art and the people of art. The exhibition reflects what we lived. Despite everything we have gone through, we can rise again. Look at us, we are making art out of pain.” She stressed that Nova Gallery operates as a nonprofit. “It felt as if God was telling me that my decision to come back to Syria was right.”

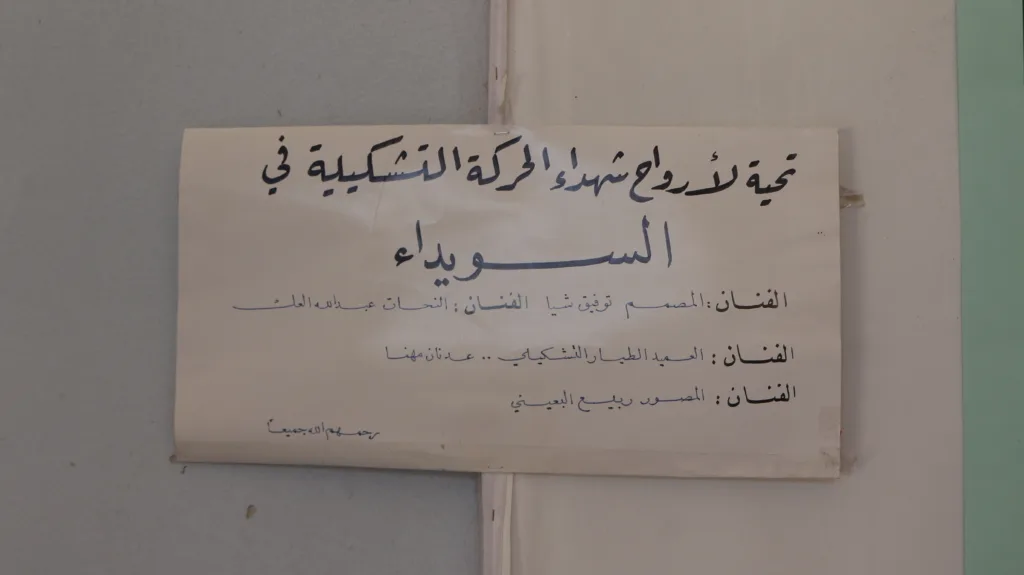

Before the first canvas, visitors met a handwritten sign dedicating the show “to the souls of the martyrs of the visual-arts movement in As-Suwayda,” naming four figures. It was not a decorative flourish. It was a frame for reading the room. The sign linked the gallery to a lived history of teaching, perseverance, and real loss. The visit began with acknowledgment, then listening, and looking inside the hall became a quiet civic act rather than a casual viewing.

From statement to gallery

The exhibition did not appear out of nowhere. On 28 July, the As-Suwayda branch of the Syrian Union of Visual Artists announced internal steps to set its professional house in order and to safeguard its legitimacy, noting the loss of artists during the events. On 5 August, the branch issued a clarification affirming its elected mandate and explaining a suspension of contact with the central executive office until internal affairs are organized. Only a few weeks later, the gallery opened and filled with visitors. This sequence, from a written position to a public practice, shows how local networks can turn decisions into action on a short timeline.

Several factors explain the pace. Close professional ties among studios, galleries, and colleagues shorten the path from planning to programming. A visual language can name pain without collapsing into partisan slogans, which broadens the circle of those willing to show up and refocuses attention on essentials. The logistics of a group show are manageable when finished works are reframed or newly completed on short deadlines. Above all, the gallery is understood socially as a common room for the city, a place of reassurance and mutual recognition, not just a wall for display.

The branch’s two statements used professional, direct language rooted in elected legitimacy and a clear relationship with the center. When that language moved from paper to a crowded hall within weeks, it strengthened public confidence that the cultural institution belongs inside the city’s civic fabric. In a hard moment, a simple model returned to view: disciplined organization, a clear message, and an action open to everyone.

In the end, As-Suwayda’s art scene offered a concise lesson in responsible response. An early stance, an institutional clarification, then a room packed with people witnessing their reality together and shaping a shared memory. The sign at the door set the ethical compass, the works supplied the language the place needed, and institutional conduct provided the frame that lets the work continue. In this way, the arts led the public moment, not because they hold solutions to everything, but because they created a space of trust that keeps dignity and memory within the city’s reach.

Dedication

The exhibition was dedicated to four late artists from As-Suwayda whose work and teaching helped shape the local scene.

Brief bios

Tawfiq Shaya

Designer and artist from As-Suwayda, trained at the Faculty of Fine Arts in Damascus. Known for functional inventions and concept pieces that reshape everyday materials into meaningful objects. A mentor to younger practitioners.

Abdullah Al-Akk

Sculptor from rural As-Suwayda and a member of the Union. Works primarily in basalt and marble. Notable for a monumental Arabic coffee pot carved from a single basalt boulder and other public works rooted in local stone and social memory.

Adnan Mhanna

Brigadier pilot and visual artist from As-Suwayda, with a doctorate in military science. Presented solo and group shows, including the “Horizons and Depths” series at the Culture Palace in As-Suwayda. His paintings explore motion, landscape, and discipline.

Rabeeh Al-Ba‘ini

Painter and art educator from As-Suwayda. Exhibited “Public Mood” in Damascus in 2014 and later in As-Suwayda. Frequent themes include nature and botanical studies, with a strong presence in local arts education.