Everything that unfolded in As-Suwayda on Saturday, 20 September 2025, can be distilled into a single placard held by an elderly woman: “Security is a right for every human being.” We chose that sign because it captures the origin of the story; everything else branches logically from it—freeing abducted women and men, opening crossings, securing justice and accountability, and, ultimately, deciding the form of governance and decision-making. Without security, every slogan hangs in the air. Once security is safeguarded, it becomes possible to speak about rights and politics in a measured, realistic way.

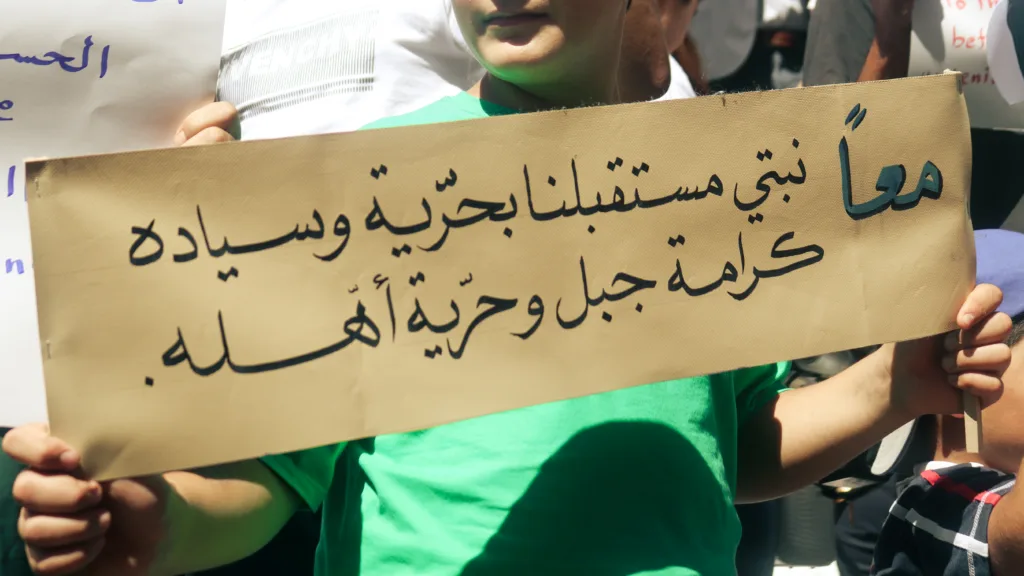

Within that frame, two headline demands led the demonstration: the right to self-determination and the release of abducted women and men. Around them, signs sketched a plainspoken roadmap: “No life without dignity and freedom.” “No peace and no reconciliation with terrorism.” “From the roots of our forebears springs freedom.” “Together we build our future with freedom, sovereignty, and the dignity of the Mountain and its people.” Practical asks appeared too, such as opening a safe, official crossing under international protection to ensure the flow of aid and essential needs. Other messages sharply criticized the closure of crossings and the tightening of restrictions on civilian movement, and warned against political-money interference and manifestations of extremism in education and administration. This was not a scatter of slogans but layered facets of a single idea: security—protecting life and liberty, safeguarding livelihoods and services, upholding justice that underwrites civil peace, and enabling political participation that places people at the center of decision-making.

Independent verification strengthens this approach. UN humanitarian reporting1 has documented that the escalation beginning in mid-July led to large-scale displacement across Suwayda, Dar‘a, and Rural Damascus; UNICEF estimated roughly 192,000 displacement movements during July alone, alongside severe constraints on humanitarian access, the use of schools as shelters, and the disruption of water and electricity. This backdrop explains why the street insists on tying big-ticket demands to concrete, measurable protection measures.

At the level of vital specifics, recent UNICEF updates2 indicate that key water installations have become “lifelines” for tens of thousands, and that the immediate response has leaned on emergency water provision, fuel support for pumping systems, and well rehabilitation, in addition to multi-sector convoys that entered the governorate in August despite access complications. In that light, the call to “open a safe, official crossing under international protection” is not political ornamentation but a precise name for daily needs without which life cannot function. [2]

The case of abducted women and men, which moved to the forefront, is no emotional aside. There can be no meaningful political conversation while entire families are suspended, waiting for news. Realism here is a method, not a mood: accurate and protected lists; trusted channels for information exchange; psychosocial accompaniment that preserves dignity; and sustained civic and religious pressure that keeps the file on the table and prevents its commodification. In this way, slogans become procedures.

On the legal flank, the community’s discourse intersects with an existing UN track: an independent, impartial investigation that preserves evidence, protects witnesses, and reorders the facts away from politicization. Hence the renewed emphasis by rights groups and humanitarian organizations that safe access for fact-finding missions, continuity of convoys, and the restoration of essential services are all necessary conditions for testing the sincerity of any “roadmap.” In the wider picture, the IOM’s Displacement Tracking Matrix3 records large numbers of internally displaced people in and around Suwayda, with a predominance of host-family sheltering and elevated needs in housing, water, and cash assistance—conditions that help explain why the street has placed security first. Social stability begins with reliable water and a viable home, before any constitutional or administrative drafting.

Here, the question of “self-determination” advances in realism rather than in maximalist pitch. In international practice, the path begins internally: accountable civil administration, fair representation, and concrete guarantees for minority rights—identity, practice, and culture. If those doors are shut and violations persist, it becomes legitimate to open a supervised consultative track under international oversight to determine the most appropriate administrative arrangement—provided all of it rests on protection and justice, not fear or coercion. This sequence is not an evasion of the “big questions,” but the shortest way to confront them without incurring further loss.

In summary, what emerged from the square was less a declaration of rupture and more a draft social contract written in simple terms: security first; then justice—closing off impunity and fortifying civil peace; then participation—returning decision-making to the people themselves. With that compass, “self-determination” regains practical meaning and steps down from the placard to the ground: the safe release of abducted women and men; the controlled opening of crossings and aid corridors; an independent investigation that upholds rights and prevents file-tampering; and, then, a popular consultation that chooses the form of administration from a position of safety. The image we began with is not aesthetic garnish; it is the first clause of any serious policy. Any step that fails to add to that woman’s security does not deserve to be called policy; anything that brings her closer to a normal day deserves to be defended and built upon. Only thus is the future written from a square crowded with slogans—by a single honest sentence in the lead, buttressed by documented facts, and followed by a cadence of steps that carry us from slogan to reality.